From the existing information made available to descendants, the story

of Erastus Chandler (EC) abounds with historical interest. And our knowledge of him is based on only a

few accounts. There was much more. Sadly, ECs story ended over 150 years ago and

many of the more personal details of his life have been lost to time. Enough exists to paint a colorful picture of

a man who experienced some of the most curious and significant, yet depressing

and tragic, moments in American history.

Note: One of those terrible

aspects of this story deals with slavery.

The life of EC could not be told without including those men and women

who were there, all the time. I

generally use the term “slave” though most records of that time utilize the

term “Negro.” Every attempt was made to

be sensitive to the issue.

EC’s story starts in Halifax County, Virginia during the early 1800s

(his father was living in Halifax County according to the 1820 and 1830

census). Halifax County’s claim to fame

was twofold. For one, Halifax County was

consistently the largest tobacco producing county in the United States. Second, and obviously related to the first

designation, Halifax County was the largest slave holding county in the United

States. EC was born on a large tobacco

plantation in north central Halifax County.

His father’s plantation was not the largest in the region but was

certainly much larger than most (exact acreage unknown though presumed at well

over 1000 acres). At the time of his

birth, EC joined a large home of about 12 Chandlers and over 70 slaves

(according to census records 73 in 1820 and 74 in 1830).

EC was the son of Willis Chandler (from the 1836 Willis Chandler will)

and wife Rebecca Hill-Chandler (Willis and Rebecca married in 1802 and she died

30 March 1834). Records indicate that

perhaps EC was the 12th of 13 children and the youngest son out of 10

boys. Father Willis Chandler was over 50

and his mother Rebecca was approaching her mid 40s. Older siblings had already grown up and moved

away from the Robert Chandler home by the time EC was born.

The year of EC’s birth date is uncertain but assorted records point to

the year 1823. Notes: In the 1830 census, EC was noted as a male between 5 and 9 –

which puts his birth between 1820 and 1825.

His younger sister was listed as a female between 5 and 9 but her birth

date is known – 16 March 1825. This

information further narrows his birth year to between 1820 and 1823 (unless

they were twins). The 1837 Mississippi

State Census possibly notes EC living with his older brothers as a male between

0 and 17 – placing his birth as between 1819 and 1837. The 1860 US Census records his age as 35

(which is the reason many descendants report his birth at 1825) but since his

sister was born in 1825, his age is assumed to have been older than 35 at that

time (since he was born before 1825 according to the 1830 census). Two Civil War records note different birth

years. A 2 March 1861 enlistment age was

36, pointing to either 1824 or 1825 as a birth year. However, a 23 May 1861 record states EC was

38 which would place his birth year as either 1822 or 1823.

The source of the name Erastus is unknown. There is no solid evidence that Erastus was a

name related either to father Willis Chandler or mother Rebecca Hill-Chandler. Erastus was, however, a biblical name from

the New Testament. Bible “Erastus” was

connected to bible “Timothy” – interesting as Timothy was a name consistently

used by Chandlers. The Chandler family

commonly honored their brothers or sisters (sometimes deceased) by recycling

first names so an unknown Erastus child (who had died young) from a previous or

concurrent generation could have been the source. Note:

There is inconclusive evidence within the Halifax County Hill family that an

Erastus Hill could have been the brother of Rebecca Hill-Chandler.

Descendants also are aware that EC had a middle name that started with

C (he was commonly referred to as “E. C. Chandler” in assorted records). Since EC’s brother John James Chandler named

a son Erastus Crayton Chandler (born 1833), I believe that our EC was more

formally known as Erastus Crayton Chandler.

The origin of the name Crayton is similarly perplexing. No Crayton’s lived in or around Halifax

County. Erastus may have also answered

to one or more nicknames. Descendants

note that EC was informally known as Ras and Ralph, but those names may have

come along later.

Current map showing true locations of Halifax County rivers, creeks,

and court houses. The approximate

location of the Willis Chandler plantation was likely closer to Willis

Chandler’s grandfather William Chandler, according to this map and the deed

below.

EC’s father Willis Chandler ran a large plantation (deeds have not been

seen but the number of slaves on the plantation indicate large acreage). An 1823 deed appears to identify a potential

location for Willis Chandler’s land. The

deed reported that an Abbott tract boundary began on Difficult Creek at the

mouth of the Double Branch where it empties into the main creek (Difficult

Creek), up the same (Difficult Creek or Double Branch?) as it meanders to the

mouth of a branch, then up that branch to John Fulkerson (who was connected to

the Chandlers), Willis Chandler, and Daniel Robert’s Mill Pond (Roberts owned

land adjoining Mill Creek). The property

was between the Double Branch and Mill Creek, just north of Clay’s Mill and

within a mile or two southeast of Crystal Hill, the location of the old court

house.

EC’s maternal and paternal grandparents had died before he was born. Therefore, EC was did not benefit from the

leadership of elders. While EC may have not developed his person traits and

skills from grandparents, there were many Chandlers to learn from. His father had quite a few brothers that

formed a strong Chandler community all around the Difficult Creek region. These men certainly shaped young EC and

helped him develop skills to become a successful and prosperous citizen.

Having been one of the youngest children in a large family, EC’s youth

involved experiencing several difficult familial events. When still a toddler of about three, his

brother Monroe Chandler passed away (1826).

At age 10 or 11, EC’s mother passed away. Rebecca Hill-Chandler was only about 54 when

she left her large family. Another

brother Jerome Chandler likely passed away before EC was 12 (approximately

1835, or between 1830 and 1836). By age

10, EC had seen several brothers and sisters leave his father’s plantation and

start their own lives. After EC’s mother

died, his 63 year old father Willis Chandler would not remarry and would rely

on his family and his slaves to care for his remaining dependents.

A Virginia map showing more details of Difficult Creek and Halifax

County road systems of 1827. EC’s

father’s land is believed to have been in the circled area.

Another Virginia map (Herman Boye, 1827) that showed Halifax County

roads with mills (red), larger county towns (blue), known churches (green), and

colleges/academies (yellow).

During EC’s childhood, his father’s plantation was experiencing

diminished productivity (as were all tobacco plantations in service for long

periods of time). Harmful tobacco

agricultural practices wreaked havoc on soil over time. Tobacco growth turned fertile fields of rich

earth to useless and unproductive farmland after extended use for even the

largest land owners. Additionally,

tobacco demand from Europe steadily waned in the early 1800s, dropping prices

and profits. EC’s father must have come

to know his children’s potential prosperity in tobacco was at risk and

therefore, he and his older children were forced to look elsewhere for profit

and success. To the southwest,

Mississippi offered the best opportunity – newly available land, cheap prices,

rich soil, and a more profitable business.

Cotton.

The 1831 Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty gave the United States full access

to Choctaw land in Mississippi. A vast

majority of the 19,000 Choctaw natives were then removed to the Indian

Territory in present-day Oklahoma.

Between 1831 and 1833, 13,000 Choctaw moved and throughout the 1830s,

the remaining Choctaw were forcibly sent west.

According to legend (Silas Chandler’s family (http://www.isnare.com/encyclopedia/User:Soulbrosampson/Silas_Chandler),

the Willis Chandler family received land in Mississippi from the federal

government as a result of the Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty signed with the

Choctaw Indians (actual evidence of this has not been found).

And so, just after EC’s mother Rebecca Hill-Chandler passed away, EC’s

siblings began to relocate to Mississippi.

Brothers Willis Chandler (about 29) and Robert Chandler (about 28)

appeared in Lowndes County, Mississippi in 1834 (Lowndes County, Mississippi

tax records, neither were reported in the 1831 or 1833 – no 1832 exists). Sister Rowena Chandler-Williams, a widow,

joined her brothers by 1835 (1845 Rowena Chandler MS court document, presented

farther below, and the Dodenhoff Chandler history, 1969) but was not listed in

the 1834 or 1835 tax record (she may have been living with her brothers or

someone else if she arrived earlier).

Rowena would not have traveled alone with her two young daughters and

therefore, Willis and/or Robert may have escorted her during treks between

Virginia and Mississippi. Once Rowena

arrived in Mississippi, she may have lived with her brothers (she also was not

listed in the 1836 tax record).

A US map, dated 1836, shows roads in the southern states. The Chandlers would have journeyed to

Columbus, Mississippi avoiding the mountains.

The trek totaled about 600 miles across the Carolinas, Georgia, and

Alabama.

Other WC children appeared to have had no intention to leave

Virginia. Other older EC siblings

Hartwell Chandler and Diana Chandler-Johnson were married and raising families

near their father in Halifax County in 1836.

Another EC sibling appeared in Mississippi by 1837. The 1837 Mississippi State Census (first year

this was conducted and every four years for next eight years) enumerations show

Robert and Kyle Chandler (enumerated together as “Robert & Kyle Chandler”)

living near Plymouthtown, Lowndes County while their sister Rowena

Chandler-Williams (enumerated Rosana Williams) lived in Plymouthtown (only 17

heads of family were listed there). Kyle

Chandler was newly married (September 1837 in Halifax County to Paulina Petty)

and brought additional slaves to supplement those held by Robert Chandler. Willis Chandler had disappeared from

Mississippi records by that time.

The 1837 Mississippi State Census record for Robert and Kyle Chandler

notes 15 male slaves and 15 female slaves (30 compared with taxes on 21, that

appears to demonstrate that 9 were under 6 or older than 59). They reported having 100 acres and may have

had more since the census only required notation of “cultivated land as of

1834.” They also produced 50 bales of

cotton in 1836 (specific census category).

Also living with the Chandler brothers was a male 0 to 17 (3 total males

lived with “Robert & Kyle Chandler”).

This was quite possibly their brother EC who was about 14 at the

time. His older brothers may have

allowed him to come help develop the cotton plantations, knowing that his

future was to be in Mississippi cotton within just a few years.

Note: Census records show

several times that WC young sons left their father’s plantation and were living

with older siblings. Therefore, the

probability of EC having been in Mississippi with his older brothers in 1837 is

quite high.

The location of Plymouthtown in an 1838 Mississippi map. The early Plymouthtown

settlement was situated on the west bank of the Tombigbee River, directly

across the river from Columbus, the site of a Mississippi Land Office.

Back in Halifax County, Virginia, the 1840 US Census noted EC’s father

Willis Chandler’s family dynamic along with the group of slaves he owned. Though EC seems to have been in Mississippi

during 1837 and possibly on into 1838, he may have returned to Halifax County

(since names are not listed on the census with only ages – members of the

family are just guesses, no youngsters were living with Chandlers in

Mississippi according to the 1840 census).

According to father Willis Chandler’s census record, only six family

members (family members are established using the 1836 Willis Chandler will

combined with Willis Chandler children found elsewhere in census records) lived

in WC’s household along with 61 total slaves.

This total demonstrates a 13 slave reduction from the previous decade

(even though 21 slave children had been born in the last ten years). WC had obviously given slaves to his children

(or they had died). The 61 slaves he

owned included 1 male 55-100, 1 female 55-100, 3 males 36-55, 10 females 36-55,

6 males 24-36, 9 females 24-36, 4 males 10-24, 6 females 10-24, 10 males under 10,

and 11 females under 10. Note: the number of slaves could have been

an estimate from a neighbor and therefore underrepresented since WC’s family

ages do not seem to be correct either. The

1840 US Census household for Willis Chandler appears as:

M60-69 WC (about 69) (Note: wife Rebecca deceased)

M20-29 ? (must have been Standfield

Chandler, about 32)

M20-29 John James Chandler (about 25)

M10-14 ? (must have been Erastus Chandler,

about 17)

F10-14 ? (must have been Rebecca Chandler,

about 15)

M10-14 ?

(wonder if this could have been grandson James Monroe Chandler who also was

enumerated with his father Hartwell Chandler)

The Willis Chandler home in the 1840s included the above items, as

noted later in the Willis Chandler 1847 inventory)

Brother Gilderoy Chandler had arrived in Mississippi by 1840, the fifth

Willis Chandler child to do so, and was living beside brother Kyle Chandler in

Oktibbeha County, Mississippi (US Census).

They were both living alone yet were joined in their households by their

slaves (Gilderoy had 14 slaves and Kyle had one slave).

In late 1840, EC was present at yet another sibling’s marriage. EC’s 25 year old brother John James Chandler

married Susan Anne Moore on 4 December 1840.

The marriage took place in Halifax County, which would be their

home. There was no evidence that John

James Chandler was involved with farming and so there was no need for him to

engage in the cotton business in Mississippi.

The Willis Chandler home had now diminished to three children that

remained under his care – Standfield Chandler, EC, and Rebecca Chandler. However, on 22 February 1844, Rebecca

Chandler married William Elbert Moseley in Halifax County and the Willis

Chandler plantation home was down to two children – Standfield Chandler and EC.

1842 Gilderoy Chandler and

Louisa Garner – Mississippi or Tennessee?

The Mississippi Willis Chandler children apparently did not have a

clear plan in place for Mississippi cotton.

After stops in Lowndes County and Oktibbeha County, they arrived in

Chickasaw County, Mississippi by 1845 (Gilderoy had purchased land there in

1841, was he there, tax

records?). Kyle Chandler, Robert

Chandler, and Gilderoy Chandler were enumerated in Chickasaw County for the

1845 Mississippi State Census (no data other than name). The 1845 Chickasaw County tax records report

a bit more information. Robert Chandler

and Gilderoy Chandler lived beside each other (tax list). Robert Chandler paid taxes on 7 slaves (6

between 5 and 59, 1 between 0 and 4), one clock, and 26 cattle. Gilderoy (Leroy in tax records) Chandler paid

taxes on 13 slaves (9 between 5 and 59, 3 between 0 and 4), one pleasure

carriage, and one clock (taxes were not paid on cattle, yet cattle were not

taxed unless the tax payer owned more than 20 cattle). Each reported one white poll (and so, no

other adult white males were in each household) and Kyle Chandler was not

listed in the tax records. None of the

Chandlers paid land tax (according to land tax records for 1845, wonder if they

were renting land to farm cotton). EC

was about 22 and was not identifiable in any 1845 Mississippi record.

Note: A Mr. William R. Hooker

had moved from Franklin County, Alabama to Chickasaw County, Mississippi by

1845 (1845 tax record, 1 white poll, 3 slaves).

William R. Hooker previously lived next to EC’s brother Willis Chandler

in Franklin County, Alabama in 1840 (1840 Alabama State Census). Brother Willis Chandler had not accompanied Hooker

to Mississippi and disappeared from Alabama records in 1842 (he was possibly

found soon after in Greenville County, South Carolina). William Hooker’s son was born in Alabama in

1842 and the next child was born in Mississippi in 1844 (actually Civil War

records note that he was born in Pontotoc County, Mississippi; William Hooker

appears on the 1843 Pontotoc County personal tax record – no record of him

there in 1842 or 1844). EC would marry

the step-daughter of William R. Hooker within the next 8 years.

In 1846, a sixth WC child had arrived in Mississippi, the first new

Chandler to be considered an actual Mississippi resident since 1840. EC, now about 23 years old, journeyed south

from Halifax County, Virginia in a pleasure carriage (taxed in 1846). He was living in Chickasaw County beside his

brothers Gilderoy Chandler and Robert Chandler at the time taxes were recorded

in 1846. Gilderoy Chandler paid taxes on

20 slaves, 25 cattle, one pleasure carriage, and one clock. Robert Chandler was taxed on 31 cattle, eight

slaves, and one clock. EC did not pay

taxes on slaves – only himself as an adult white male. These three Chandlers appear to have lived

somewhere near William R. Hooker.

By 1846, EC was a full grown, unmarried adult man at about age 23

years. He stood 5 feet, 11 inches in

height, which was taller than the average North American man at 5 feet, 7

inches (his height was reported in Civil War papers). His complexion was fair and his hair color

dark (Civil War papers). His eye color

was blue (Civil War papers). Finally,

EC’s occupation was, not surprisingly, a farmer (Civil War papers, 1860

Census). Chandler’s were raised as

tobacco farmers and the family was surely also adept with growing food crops

along with other living necessities.

In 1845, the independent republic of Texas had joined the United States

as the 28th state. Mexico was not happy

with this and declared war on Texas and the United States. After some hostilities on the Texas-Mexico border

in early 1846, the US Congress declared war.

Congress asked for regiments of troops which included one regiment of

1000 men from Mississippi. Since there

were many families in Texas from Mississippi and an interest in expanding the

number of slave holding states, Mississippi men underwent a wave of war

fever. 17,000 Mississippi men were at

Vicksburg, Mississippi to volunteer.

However, 1000 were chosen and the remainder sent home. Could EC have been present at Vicksburg to

volunteer as a soldier? The Mississippi

regiment fought in 1846 and lost 200 men.

They continued to fight throughout 1847 and into 1848.

EC had left his father Willis Chandler (in about 1845 or 1846) under

the care of his older brother Standfield Chandler and Chandler slaves – who

largely kept the house and operated the tobacco plantation. The elder Willis Chandler was about 75 at the

time his youngest son journeyed to Mississippi.

More than likely, it was the last time EC would see his father. On 10 September 1847, father Willis Chandler

passed away (Mary Eugenia King Province bible, owner Mrs. Vernon Gomez of

Austin TX, from “Virginia Bible Records” by J. H. Austin). The will was brought to Halifax County court

in November 1847 and then in December 1847 (Halifax County Probate Records). In December 1847, a few Willis Chandler

family members purchased items at the estate sale - John James Chandler,

Hartwell Chandler, Thomas Johnson (husband of Diana), William E. Moseley

(husband of Rebecca), and Standfield Chandler.

After their father’s death, EC’s brother Standfield Chandler and sister

Rebecca Chandler-Moseley decided to leave Halifax County and join their

siblings in Mississippi. Both Standfield

and Rebecca were last noted in the WC estate records at Halifax County in

December 1848 (payment to WC estate through brother Hartwell Chandler) and were

at Mississippi in October 1850 (US Mississippi Census). And so, the seventh and eighth child of WC

had arrived in Chickasaw County. The

eight Mississippi WC children are noted below with approximate immigration

dates.

The 1848 Chickasaw County tax records show that EC was definitely the

low Chandler regarding pecking order.

Four brothers were taxed in Chickasaw County – Kyle, Robert, Gilderoy,

and EC. Kyle Chandler appeared to live

apart from the others (taxed at different time). He paid for taxes on one white poll and 28

slaves ($17.20 total). Robert, Gilderoy,

and EC were taxed at the same time.

Robert Chandler was taxed for one white poll, 17 slaves, and 35 cattle

($11.05 total) while Gilderoy Chandler paid taxes on one white poll, 15 slaves,

and 40 cattle ($9.80 total). EC was

taxed for one white poll (paid $1.15 total) and was taxed for no slaves and did

not have a herd of cattle over 20 head.

More than likely, EC’s brothers paid taxes for him (slaves and other

assets) in the early stages of his time on his own. There seems to be no doubt he had slaves from

his father’s estate.

Many counties kept a record book titled the Sheriff’s Book. In these records, the county clerk entered

details of county citizens against whom the county issued warrants that were to

be made for recovery of debts. In the

1848 to 1850 Chickasaw County Sheriff’s Book, each Chandler brother was listed

– EC, Kyle, Robert, Gilderoy, and Robin (?).

The information in the book that was associated with each Chandler has not

been seen.

EC and his brothers moved from Lowndes to Oktibbeha to Chickasaw County

by 1850. This map shows the county

boundaries that were consistent for these counties from the 1830s through the

1850s.

On 9 June 1849, four men from Chickasaw County were recorded by the

county sheriff at the same time in the Chickasaw County bond book (Bond

Book for Chickasaw Co MS officials, 1847-52).

Three of these men were known to have been residents in the area around

the small town of Palo Alto, Chickasaw County – Gilderoy Chandler, John E.

Clark, and Norman Robinson (from land taxes identifying land location). The fourth was EC (this connects EC to the

Palo Alto region). The men were bound to

a bond (promise to make payment) for Edward F. Clowdis. Each of the four bound men were single and

probably connected as acquaintances through living proximity. John E. Clark was 29 and a single (but would

marry within the next few months) farmer from Alabama. Norman Robinson was 26 and a single (he took

care of his parents) farmer from South Carolina. Edward F. Clowdis was 22, a single farmer,

and lived near EC’s sister Rowena south of Chickasaw County in Oktibbeha

County.

According to the Old Attic Records for Chickasaw County, EC was charged

with gambling in 1850 (Chickasaw Co MS Circuit Court files, 280, p

258). EC was specifically accused of

playing a game called “ten pins” in a case known in the record books as “the

State versus Erastus Chandler.” Concurrent

record notes that George W. Dunn and William G. Hightower were charged in the

same way at the same time. Hence, EC,

George W. Dunn, and William G. Hightower were likely gambling together. Ten pins was essentially today’s bowling. The game had become popular throughout the

1700s in the United States and was usually played illegally as a gambling

activity. Alleys were created and both

pins and balls were made of wood.

William G. Hightower was a 23 year old farmer from Georgia who lived in

the Palo Alto area near Gilderoy Chandler and Robert Chandler. Calvin Hooker (EC’s future brother-in-law),

the brother of William Hooker (EC’s future father-in-law), was also charged

with gambling at the same time (but not noted as ten pins).

An 1853 Mississippi map and the approximate locations of the Eastern

and Western District Chandlers.

Chandlers in the Western District were near Sparta and those in the

Eastern District were near Palo Alto.

Identified on the map are EC (1), William Hooker (2), Gilderoy Chandler

(3), Rebecca Moseley (4), Standfield Chandler (5), and Kyle Chandler (6). Note Montpelier appears to have been

originally located just east of its current location.

EC was not enumerated in the 1850 Census. He had most likely traveled to another

location and was absent during the census enumeration (as records place him in

Chickasaw County in 1849, 1850 and 1852). Note: EC may have simply been missed by the

census taker. The way families were

enumerated provides information about where EC might have lived in the early

1850s. In 1850, EC’s Chandler siblings

and close associations were enumerated in two locations. Brothers Gilderoy Chandler and Robert

Chandler both lived in the Eastern Chickasaw County District (as noted in the

1850 census) at a location adjoining the town of Palo Alto. Also in this district was William Hooker (EC

married into this family), Calvin Hooker (husband of his future sister-in-law),

and Joseph Dunlap (Robert Chandler and Standfield Chandler married into this

family). The town of Palo Alto is

located at Township 16 South, Range 5 East, Sections 17 and 20. EC was taxed on land in Section 12 and 13 of

Township 16 South, Range 4 East which also adjoined the Palo Alto town

area. Gilderoy Chandler owned land at

sections 7, 8, and 18 adjoining the Palo Alto town sections and William Hooker

owned land at section 18. The town of

Palo Alto appeared to be very small in 1850 (the town began in 1846, according

to historical accounts). There was a

hotel run by Daniel B. Hill, several physicians, a clergyman, and a blacksmith

(1850 census occupations of those enumerated together in Palo Alto).

Note: EC likely lived at this

location near Palo Alto along with his two brothers Robert and Gilderoy, and

his future in-laws – the William R. Hooker family. The men he was associated with, per Chickasaw

County records for 1849 and 1850 (previously noted), were here as well. See below for 1850 census enumerations of men

associated with the Chandlers who appear to have lived in and around Palo Alto.

EC could have also lived near his Chandler siblings and associated

families found enumerated in the Western Chickasaw County

District. According to land ownership,

this location was between Sparta and Montpelier – towns that had yet to become

fully established. The distance between the

“Eastern” and “Western” designations appear to have been only about five to

eight miles. These Western District

Chandlers were Kyle Chandler, Standfield Chandler, and Rebecca

Chandler-Moseley. Associated families

living in the same community were the Brownlees, Davidsons, Cousins, and Fords,

among others. The census reveals no

obvious town locations nearby (usually identified by a group of families that

ran town businesses), other than a few arbitrarily enumerated blacksmiths and

teachers.

Living in Oktibbeha County south of Chickasaw County was EC’s sister

Rowena Chandler-Edington and her husband Philip Edington (page 291B). They had been married for 11 years and their

two children Alena (3) and Joseph (1) were living on their small plantation

along with 5 slaves (some records of Rowena report another child Rosebud

Edington but Rosebud Edington appears to have been Philip Edington’s child by

his second wife). According to the

census, Philip Edington was a farmer and held real estate with a $1200

value.

Though EC was not listed in the 1850 census, he was certainly there

(other records). And EC probably owned

about 20 slaves at that time (he was taxed on 19 slaves in the 1852 Chickasaw

County Tax Book). EC was about 27 years

old in 1850. He was operating a cotton

plantation and certainly would have had a home on his land with slave

houses. The plantation was prepared for

a mistress (common name for a slave master’s wife) but EC had not married yet. The owners of slaves (slave “masters”)

commonly had children with one or more of their slaves. In late 1850, one of EC’s female slaves gave

birth to a daughter named Josephine.

Josephine’s mother was surely a house servant (as opposed to a field

worker). Mothers of a master’s illegally

sired children were or became house servants who cooked, cleaned, and lived in

the plantation home. Notes: Various census records point to 1850

or 1851 as Josephine’s birth date. Also,

the mother of Josephine is assumed to have been named Minnie (or Mindy). According to the 1870 census, Minnie was the

mother of Josephine’s known younger brothers (information from Josephine’s

descendants who had been told this by older relatives) Booker and Brooks.

Since before EC was born, the controversy regarding slavery had been

steadily dividing the US population. The

northern states were opposed to slavery and viewed slavery as inhumane,

barbaric, and heartless. The people of

the south disagreed. They viewed

Africans as “so far inferior that they had no rights” (according to Chief Justice

Roger Taney, 1857). The Missouri

Compromise of 1850 was an agreement between the north and south. The north got a win – preventing the addition

of slave holding states to the west. The

south got a win – the northern population was required to capture and return

escaped slaves to the south (The Fugitive Slave Act). The attempt to quell murmurs of southern

cessation from the United States through the compromise was only temporary and

nobody ended up content. And then,

Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin (the second best-selling book

in the 1800s) in 1852. The deplorable

living conditions of slaves stunned northerners. Southerners were not happy about the book and

complained that slavery was not as bad as Stowe has made it seem. But in most cases, it was.

EC was taxed as a white poll (white male over 21) in the 1852 Chickasaw

County Tax Record. He was also taxed on

a clock worth approximately $10 and 19 slaves between 0 and 59 years of age. He lived next door to James E. Coats who may

or may not have been his brother-in-law at the time (EC married James E. Coats

older sister between 1850 and 1853).

Unlike in previous tax records, all the Chandlers were taxed at

different times – this is known since they were not recorded in the tax records

side by side. Gilderoy Chandler was

taxed near EC. He was taxed on 2

pleasure carriages worth about $300, a clock worth $10, 40 cattle, and 19

slaves aged 0 to 59. Also Robert

Chandler was nearby (the proximity to EC and Gilderoy Chandler may validate

their location at this time in Palo Alto) – taxed on a pleasure carriage ($70),

clock ($5), and 13 slaves under 60 years old.

Standfield Chandler and Kyle Chandler represented the brothers who were

furthest from EC (not surprising since their land was closer to the

Sparta-Montpelier region). Standfield

Chandler was only taxed on 18 slaves under 60.

Kyle Chandler paid the greatest taxes – a watch ($100), a race track, a

Bowie knife, a special horse worth $150, and 31 slaves under 60. Rebecca Moseley’s husband William Moseley was

also taxed on a pleasure carriage ($100) and 23 slaves under 60. An interesting notation is the taxation of

“Chandler and Fuller” who paid taxes for the sale of $1350 in merchandise within

a merchant store. No white polls were

claimed and the only Fuller in Chickasaw County was Ezekiel Fuller, who was a

farmer. Paying taxes on merchandise is

evidence of the operation of a merchant store.

Note: Robert Chandler may have

been this Chandler involved in merchant business as he was later specifically

taxed on merchandise sales in tax records.

EC was taxed on land near Palo Alto in 1853 (yellow). According to the 1853 tax record, brother

Gilderoy Chandler (orange), Joseph Dunlap (green), William R. Hooker (blue),

and others (red writing) were nearby.

Between 1850 and 1853, EC married Delphia Jane Coats. At the time of their marriage, the name

Delphia Jane Coats was probably not how she was known. The 1850 census lists her as Delpha J.

Hooker, the child of William R. Hooker (who was her step-father, this took me

20 years to uncover!). Chandler history

has passed down a story that this Delphia married first to a man named “Coyle”

who died the day they were married. No

Coyle families are found in Chickasaw or surrounding counties but there were

several “Cole” families. And the only

eligible Cole male that would fit as a first husband of Delphia Jane Coats, and

who died between 1850 to 1853, was Cicero Cole. Note: Cicero Cole was in the

1850 census but not the 1860 census. Tax

records show Cicero Cole present in the 1850 tax record but none after. All other eligible Cole men were present

through all early 1850 tax records (William J Cole 1848, 1850, 1852, 1853,

1856; Thomas C Cole 1848, 1852, 1853, 1856. Stephen Cole 1848, 1850, 1853;

Joseph M Cole 1850, 1852, 1853; John Cole 1850, 1852, 1853, 1856). He was the oldest child of Stephen and Martha

Cole of Georgia. They had moved to

Chickasaw County between 1844 and 1847.

With almost complete certainty, EC and Delphia were married by 1853

(they had a child in 1854). Early age

marriages were rare among the Willis Chandler sons and EC was about 30 or

possibly a bit younger when this marriage occurred. Delphia was probably about 19 years old

(according to her tombstone birth year at 1834). EC was surrounded by close Chandler family

members, mostly older brothers, and the event was certainly a cause for

celebration. Neither EC nor Delphia had

a birth father present. Delphia would

have been accompanied by her mother and step-father.

The 1853 Chickasaw County Tax Rolls demonstrated circumstances similar

to 1852 for EC and his siblings. EC

individually paid taxes on himself and 17 slaves under 60 years of age. His neighbor James E. Coats, who by now was

certainly his brother-in-law, again paid taxes on only himself. EC’s wife Delphia had married into a family

with a significantly more established social class than the Coats or Hooker

social status (from tax records). EC

siblings Gilderoy Chandler, Standfield Chandler, Robert Chandler, and Rebecca

Moseley were taxed as well. And again,

the Chandler & Fuller partnership continued to work as merchants selling

$3700 in merchandise. Also, EC’s step-father-in-law

William R. Hooker (4 slaves) was taxed.

Missing was brother Kyle Chandler.

EC had a second child with one of his slaves. This child was born on 1 July 1853 (according

to Seminole County, Oklahoma records) and was named John Booker (no surname,

commonly known as just Booker). Booker’s

mother is assumed to have once again been the EC slave Minnie (also known as

Mindy, 1880 census). Note:

In 1870, Booker was a mulatto boy of 18 and lived with Minnie and her

husband Warner. There were six other

children. In 1880, the youngest of these

children was listed as the step-child of Warner. Hence, Warner was not the father of

Booker. Descendants of both Josephine

and Booker report EC was commonly known as their father.

The 1853 and 1854 Chickasaw Land Tax records also provide information

on Chandlers and their neighbors (below).

Note: the 1854 land tax record

demonstrates inconsistencies in tax payments for sections they previously paid

taxes on in 1853. Did this mean the land

was rented, leased, or owned? County

deeds may be able to sort these issues more thoroughly. I have not seen those records.

1853 Chickasaw County Land Tax records

1854 Chickasaw County Land Tax records

A Clay County, Mississippi Township-Range map. The green boxes show sections that Chandlers

and associated families were associated with between 1840 and 1860. These families all lived within ten miles of

each other.

On 16 May 1854, EC’s brother Gilderoy Chandler died. Only two months earlier, Gilderoy Chandler

had turned 40 years old (tombstone inscription). He left his wife Louisa Garner-Chandler a

widow with three young boys – Andrew, Benjamin, and Kyle – between age 6 and

11. Note:

He had a daughter Virginia that recently died in 1853. The family buried Gilderoy Chandler at

Palo Alto in the Chandler Cemetery (current name of the cemetery). The cemetery was the final resting place of

several different families, including Aycocks, Coopwoods, Edingtons, and

Hearns. According to land records and

map location, this cemetery was in section 8 of Gilderoy Chandler’s land. Marked stones note that at least six burials

took place there prior to Gilderoy (listed as Roy on his tombstone) Chandler –

Lucy Aycock (1843), Isaac Aycock (1845), James Aycock (185), William Aycock

(1852), Virginia Chandler (1853), and E. T. Hearn (1853). Note:

The widow Louisa Garner-Chandler would raise her children with the help of

their slaves and would not remarry (she was taxed on cotton in 1866). She was buried at Chandler Cemetery in Palo

Alto in September 1867.

The Chandler Cemetery just north of Palo Alto on Gilderoy Chandler’s

land

Gilderoy Chandler was buried at what is currently known as Chandler

Cemetery. The location of the cemetery

(large orange circle) is located on Gilderoy Chandler’s land (marked light orange).

By February 1854, EC’s wife Delphia Coats-Chandler was pregnant. On 19 October 1854, Delphia gave birth to

EC’s first legal child, a baby girl. Note: Mississippi law did not recognize

children of slave owners as “legal” children.

These children were to be considered property and were to be treated as

slaves. EC and Delphia Jane

Coats-Chandler decided to name their new daughter Virginia Chandler. The name certainly was connected to EC and

Delphia’s true birth place and family home - Virginia. A consistent Chandler tradition was to name a

child after a recently deceased nephew or niece. EC’s deceased brother Gilderoy Chandler had a

daughter born 10 October 1852 named Virginia Chandler. This child (EC’s niece) had died just after

her first birthday on 12 October 1853 (tombstone at Chandler Cemetery). EC’s daughter’s name was unquestionably

adopted as a tribute to EC’s deceased niece.

On the first day of the 1855 year, EC’s sister Rowena Chandler-Edington

died (Chandler Cemetery tombstone, spelled Roena Edington on her

tombstone). She was only 50 years old

(her birth date on the tombstone was 1804).

Rowena was living in Oktibbeha County (1850 census and her husband was

there in 1860) and was buried at the cemetery on Gilderoy Chandler’s land just

north of Palo Alto, Chickasaw County.

She left her husband with two very small children Alena (10) and Joseph

(about 7). Later in the year on 19

September 1855, Rowena’s daughter Alena also passed away the day before her

11th birthday. Alena Edington was buried

beside her mother at Chandler Cemetery, Palo Alto, Chickasaw County.

EC wrote his will in August 1855 at about age 32. There are several

reasons this may have been the case. EC

knew that life was unpredictable as his brother had just died the year before

at the age of 40 and his sister had died 8 months before at age 50. In his will, EC stated that at that time, he

was “sound of mind but [knew] the uncertainty of life and the certainty of

death.” With his first lawful child born

just 10 months before, EC may have been concerned with the fate of his

plantation and wanted to make sure his assets were distributed according to his

wishes if something were to happen to him.

Since he was young with a new family, he was not specific about the

division of his assets, naming only his wife and lawful heirs.

EC named William E. Moseley, the husband of his younger sister Rebecca

Chandler-Moseley, the executor of his will.

If Moseley denied the task or if he was dead at that time, EC asked that

the county court judge name an executor.

Why did EC not name one of his older brothers as an alternate

executor? Either EC thought his older

brothers might not fairly divide the assets, believing they had a legal right,

for example, to EC’s slaves…or, EC thought his brothers might not agree or

follow the wishes he made in his will.

Possibly the main reason for EC’s will at this time (from the high

level of attention and depth EC gave the situation) was to provide specific

instructions for the support of his “servant girl Josephine.” Josephine was about 3 or 4 years of age at

this time. In actuality, this “servant

girl” was his illegitimate daughter Josephine.

He would have been required by law to state this was his servant girl

since it was illegal to claim that he had fathered a child with a slave. These directions regarding Josephine were by

far the most complex and descriptive of all the items in the will. EC’s directions showed that he not only

wanted Josephine to be provided her freedom but to be raised by his family –

presumably his wife and children – until she turned 18 years old. And then after she turned 18, she was to be

given $1500. Finally, she was to be sent

to a non-slave holding state with all expenses paid. EC did not provide for any other illegitimate

children, servants, or illegal heirs.

Erastus C. Chandler Will, 1855

In the name of God Amen, I Erastus C. Chandler of the county of

Chickasaw and state of Mississippi being of sound mind and knowing the

uncertainty of life and the certainty of death do hereby make and publish this

my last will and testament. To Wit

Item 1st I

will and desire that all my just debts be paid after my death.

Item 2nd I

will and bequeath that my estate real and personal (after the payment of my

just debts) be equally divided between my wife Delphia J. Chandler and the

lawful heirs of my body, my said wife to receive a child’s part of my said

estate.

Item 3rd I

will and bequeath that my servant girl Josephine receive her freedom at my

death, that she be permitted to remain in my family (and be fed and clothed out

of my estate) until she becomes eighteen years of age and that she then

receives the sum of fifteen hundred dollars out of my estate, and that her

expenses be ---- to some one of the non-slave holding states of the United

States.

Item 4th I will

and bequeath that each of my children receive a good English and classical

education.

Item 5th I

will and bequeath that at the death of my wife Delphia J. Chandler that portion

of my estate which she may have received be returned back to the heirs of my

body.

Item 6th I

will and bequeath that my estate be kept together for ten years, then a

decision to take place, and I hereby appoint William E. Moseley my executor of

this my last will and testament, and if he should be dead or refuse to serve in

that capacity, I then rely upon the judge of the probate court.

In testimony whereof I have here unto signed my name and affixed my

seal this – day of August AD 1855.

Signed sealed and acknowledged in the presence of Daniel Brown Hill

(hotel keeper and doctor at Palo Alto), Robert Sydney Witherspoon (doctor who

lived at Hill’s Palo Alto Hotel in 1850), James E. Coats (EC’s brother-in-law

of Palo Alto)

Signed Erastus C. Chandler

Note: The witnesses for EC’s

will seem to demonstrate his continued presence at Palo Alto since they were

all Palo Alto residents. Or, maybe he

visited the town to complete his will since it was one of the larger towns in

the area.

Dr. Daniel B. Hill and his wife Margaret who both lived and died at

Palo Alto

Life continued as normal for the Chandlers. In 1856 (according the Chickasaw County

Personal Tax records), Gilderoy Chandler’s widow Louisa (as “Mrs. Louisa

Chandler”) was living at Palo Alto beside Robert Chandler and EC’s

brother-in-law James Coats (taxes recorded next to each other). EC’s stepfather-in-law William Hooker was

also taxed nearby, as was Hooker’s brother Calvin Hooker (who had married EC’s

sister-in-law). Oddly, EC was not listed

though the actual records appear to be missing a page or more of the C

surnames. Note: EC’s absence from close proximity to these men may indicate a

movement from Palo Alto to the Sparta-

Montpelier region.

Montpelier region.

Again EC had another child with his slave in about 1856 (various census

records place this child’s birth date between 1854 and 1860). EC’s slave birthed a son who was named

Brooks. Brooks has been identified by

some descendants as the son of Minnie and her husband Warner. However, the 1880 census for Warner and

Minnie (Mindy in that census) identify Warner as merely a step-father (and

family tradition states Brooks was the son of EC). Warner and Minnie must have married about

1860 to 1865. Brooks has commonly been

known as the younger brother of Josephine and Booker – and the son of EC.

The family of EC’s daughter Josephine reports that she was raised in

the EC home as one of his children. In

1856, Josephine was only about 4 or 5.

Though she was said to have been raised in the EC house, she may have eventually

be asked to perform some duties as a house servant (but likely not at this

early age). Slave masters commonly had

children with their slaves. Normally,

this presented the mistress of the home (the slave master’s wife) with feelings

of jealousy and usually led to abusive behaviors toward the illegitimate child

and the child’s mother. Josephine’s

descendants report that Josephine was treated well. No information is known about the treatment

of Josephine’s mother. Note: Sheila Glen-Cole (ss77cole@hotmail.com)

talked to her mom’s 95 year old first cousin who was Josephine’s great

granddaughter and remembered hearing Josephine reminisce about her early

years. There is another story about this

cousin’s mother (Josephine’s granddaughter) going to Mississippi in the 1950’s

to straighten out some issue with Chandler family members.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 had barely passed in Congress two years

before, overturning all previous attempts by northern politicians to limit

slavery. This act had introduced popular

sovereignty – the ability of a state to vote on slavery. 1856 marked a presidential election that was

influenced largely by slavery matters.

Democrat James Buchanan endorsed popular sovereignty and believed states

should be able to decide themselves whether to allow slavery or not. Buchanan warned that if the Republican

nominee John Fremont were to be elected, a civil war might follow. With a complete lack of support in the south

for Fremont, Buchanan won the election in November 1856. EC and all slave holders in Mississippi were

supporters of the Democrat party and voted for James Buchanan (a Buchanan vote

from EC is assumed since he was a slave owner).

EC was taken to court by Mary

Lewis in 1857 and the court ruled that EC would be indebted to her for $400

(Chickasaw MS Time Past, volume XVI, number 4, 1998, 3964, page 3833, also Old

Attic Records). Note: I have not seen the full record and do not know the reason for

this judgment. Mary Lewis was a

recently widowed farmer who lived next to William Dobbs, John Cousins, and

George Ford in the Western District.

Since these men were from Sparta-Montpelier, Lewis’ location was

certainly at Sparta-Montpelier and the connection between EC and Mary Lewis may

demonstrate that EC was living in the Sparta-Montpelier area by 1857. Mary Lewis had come to Mississippi with her

husband in about 1844 and between 1848 and 1850, her husband had died. In 1850, Mary Lewis was the head of her

family, was a farmer, and had nine children age 2 through 22.

Land tax records are available

for Oktibbeha County, Mississippi in 1857 (not Chickasaw County). Present in these records are EC’s

brother-in-law Philip Edington (though his sister Rowena Chandler-Edington was

now dead) and brother Kyle Chandler. Both men owned large tracts of land and

probably operated their cotton plantations at that location. Edington was located at Township 20, Range

15, Section 13 and Township 20, Range 14, Section 18. Kyle Chandler held land

at Township 19, Range 15, Sections 21, 22, and 27. Note:

Kyle Chandler held land in both Oktibbeha County and Chickasaw County. He may have lived in Chickasaw County (he

was buried at West Point, Clay County, in 1878).

On 25 December 1857, the first

railroad station opened its doors in Chickasaw County. The Mobile and Ohio Railroad had used the

eastern portion of Chickasaw County when they laid tracks from north to

south. Railroad depots were placed in

Okolona and Egypt. Transportation had changed. Citizens were now linked more easily to

distant locations. A wealthy cotton

plantation owner could now travel conveniently, quickly, and to more distant

locations.

By the start of 1860, EC had been

married for about seven (7 to 10 actually) years to Delphia Jane

Coats-Chandler. EC and Delphia’s

daughter Virginia Chandler was 5 years old and would turn 6 later in the year

(October). EC was about 37 and his wife

was just 25 years old. Delphia Jane

Coats-Chandler was also about eight months pregnant at the beginning of

1860. On 12 February 1860, she gave

birth to a baby boy. EC’s new son was

named Michael F. Chandler and would be called Mike. With nearly six years between children, the

couple had probably had some unfortunate luck with producing offspring. Whether these children were born and died or

never made it to full term is unknown.

A 1909 Mississippi Soil Survey demonstrated the poor soil quality of

the EC land (yellow) and William Hooker land (blue) near Palo Alto. This soil, known as Oktibbeha Clay, may have instigated

their movement to Sparta-Montpelier.

According to the 1860 United States Census for Chickasaw County,

Mississippi, EC was living at the region between Sparta and Montpelier (1860

MS Census, Chickasaw Co, Division No 1, Dalton Post Office, August 31, dwelling

917, p 162). Note:

The location of EC is reviewed shortly.

He was farming land valued at $4800 (Census records and Chickasaw

Times Past, volume 11, number 1, 1992 state the value was $10 per acre so he

had 480 acres). His immediate neighbors were George Ford,

John Cousins, father-in-law William Hooker, George McKinney, and his

brother-in-law William Moseley, who all had large farms themselves. EC (35) had a small family of four, including

his wife “Delphi” (22, born in Virginia), daughter Virginia (6, born in

Mississippi), and son Mike (6 months, born in Mississippi).

EC’s personal property (as per the 1860 census) was valued at $28,000 –

which was probably due to his slave holdings.

The 1860 slave census reports five slave houses on EC’s plantation that

included 25 slaves (1860 Slave Census Chickasaw Co MS, Division 1,

August 20, p 366). The Slave Census did

not include names but did note individuals by age, gender, and race (mulatto or

black). Note: EC’s probate records include several documents over 3 or 4 years

(between 1863 and 1867) that included the names of EC’s slaves. These slaves took the surname Chandler after

emancipation in 1865. Careful inspection

of the 1870 Census identifies the former slaves and the list below is an

attempt to place names from those future records on EC’s 1860 slave census

descriptors.

Notes: These are just guesses based on slaves found

in EC’s estate between 1863 and 1867…and the 1870 census. There were others that were in those estate

records that don’t seem to fit.

Therefore, these guesses are more than likely not to be considered

completely accurate. Also, the ages and

ethnicity of the slaves were probably not indicative of whether they were fully

African decent or if they had European blood.

Only two of the slaves in 1860 were listed as mulatto. According to census taking policy, the census

taker merely observed the slaves (or were told), and then marked them as

mulatto if light skinned and black if dark skinned.

Josephine Chandler may have been listed as a slave but EC did not treat

her as one (I wonder why Booker was not included in the will? I wonder if this had to do with skin color or

gender?). She did not work in the EC

plantation fields (according to her grandson Rush Davidson) and was raised in

the EC home with EC’s white children Virginia and Mike (according to

Josephine’s great granddaughter as retold by Sheila Glen-Cole). As she grew older, Josephine may have had

some service role but that work was in the EC home and not what was expected

from other EC slaves (according to Sheila Glen-Cole). Note:

The stories about Josephine’s childhood may be further confirmed as Josephine

named her third son Erastus, presumably after her biological father EC.

EC and his neighbors lived between Montpelier and Sparta, in Township

15 (marked in blue), and within sections 19, 26, 25, 30, 35, 36, and/or 31

(placed on a 1909 map). The darkened

black lines follow roads between Sparta and Montpelier and this (along with the

dwelling markings of 1909 denoted as black dots) probably shows the locations

of most of these family’s homes. The

entire area was Chickasaw County in 1860 but after 1872, Colfax (later Clay)

County was formed from southern portions – yellow line. Also, Montpelier and Sparta are located in

Township 3. Township 4 begins several

sections to the east. Note that the

names/locations only identify what I know.

Notice that there are many locations not identified with a name.

Note: A Chickasaw County court

record from 5 December 1864 shows that Standfield Chandler was the overseer of

Gardner Road, going from Cane Creek Bridge south to a road the led from Grenada

in the west to Columbus to the southeast.

This road must have been the right black road above that ran from

Montpelier to Amity Baptist Church.

There were several men whose slaves were to be used to maintain the

road, including the slaves of Mrs. Erastus Chandler, who surely lived along

this road. My guess at this time is

within section 36.

The census analysis above was conducted to determine the approximate

locations of EC and his neighbors. In

1860 (according to the 1860 census), these men lived in an area served by a

Dalton

Post Office. The town or small

community of Dalton is extinct and only one map (1865 Mississippi map, and I

have searched most of them) places Dalton in this area – located in what

appears to be the later location of Pine Bluff (or possibly Dixie – noted in

only a few maps between Pine Bluff and Sparta), just west of the

Sparta-Montpelier region. From the 1860

census, Dalton must have been near Montpelier (in 1860 the Montpelier Post

Office served only a few families) and Sparta.

Some of the EC neighbors (not listed in the analysis) were noted as

being served by the Big Spring Post Office in 1870. There were other men served by Dalton Post

Office in 1860 (about 10 families) but in 1870, the census noted their location

as Township 16-Montpelier and were most likely from sections 3, 2, 1, and 6 of

the map above (and possibly slightly west as well. The map above places EC’s neighbors onto a

map of the Sparta-Montpelier region. EC

and his neighbors were placed on the map by using Chickasaw County tax records

from 1853, 1854, and 1868. There are

probably other sources that could add to this information and tax records

demonstrate much buying and selling of land.

Therefore, the map does not show the exact location of homes, merely

general location. EC, for one, probably

bought, owned, and lived on land north of the Township 16-Montpelier land he

owned as demonstrated in the map.

An 1865 map shows the Sparta-Montpelier region framed by Egypt and West

Point, depots on the Mobile-Ohio Railroad at the east side of the map. Note Montpelier slightly east of its current

location.

EC owned 40 acres of land located

at Township 16 south, Range 3 East, Section 1, NW at an unknown date (noted on

map above, Chickasaw Times Past, volume 11, No 24, 1993). Within two miles to the north were his

brothers Kyle Chandler, Stanfield Chandler, and sister Rebecca Jane

Chandler-Moseley. Within 10 miles west

were brothers Robert Chandler and the home of deceased brother Gilderoy

Chandler.

In 1860, EC was no longer living at Palo Alto. But, he had family in Palo Alto and may have

still owned land there as well. The town

was now a larger community (the second largest in Chickasaw County) and was

probably often frequented by EC. Its

proximity to the small creek called Long Branch provided access to the

Tombigbee River and the Mobile, Alabama port for cotton exportation. Hence, the town provided an export point for

farmers in the area who needed to sell their crop.

A Palo Alto hotel was run by William Linn and his family. Daniel B. Hill now served the community as a

physician. His son Samuel Hill was a

physician and another son William Hill was a lawyer. Another hotel (the Palo Alto Inn) was kept by

John L. Armistead and his wife. Thomas

Bailey, James P. Deans, and William Ragsdale were also physicians. The blacksmiths were Gabriel Allen and David

Maloney. William P. Malone was a dry

goods merchant and Benjamin F. Clark (different man than Benjamin Clark from

Sparta-Montpelier) was a merchant. Simon

McKinney and Silas Clark (different man than Silas Clark from

Sparta-Montpelier) were dry goods clerks and Calvin Weaver

was a retail grocer. One or more of these stores

served as general stores where visitors bought goods that included hats, boots,

shoes, hardware, cutlery, saddles, piece goods, bonnets, jewelry and groceries. One or more of the stores must have offered

the community the goods offered by a drug store – selling medicine and even

alcohol.

Palo Alto appeared to be a center for coach and carriage

production. John D. Mitchell was a

harness maker. John Isaac was a coach painter.

John K. Allen was the wheelwright.

John Hellanther was a carriage trimmer.

Charles Cain was a carriage maker.

P. A. Hughes was a coach manufacturer and J. B. Freeman was a coach

trimmer. In addition to coaches and

carriages, A. M. Barry was the Post Master and Milton Landsford was a

carpenter. The town was of course

surrounded by farmers. There was

definitely a school as some children were noted as attending school (but not

all).

Note: According to the

Township-Range map, Palo Alto covers Township 16 South, Range 5 East, Sections

17 and 20. Tax records from this time show

these section land owners include many of the business men listed above – David

B. Hill, Clark and Clark Store (Silas and Benjamin Clark), William P. Malone,

Simeon McKinney, John L. Armistead, J. C. Weaver, S. Dean, John D. Mitchell,

John K. Allen, Hughes and Brother, and William Linn.

The small town of Montpelier (red) appears to have been located east of

the current location (yellow). Old maps

(like this North Mississippi Railroad map from the 1870s) show Montpelier east

of Palestine and closer to the small town of Big Springs. A road is also currently found in this area

called the “Old Montpelier Road.” Note that Dalton was likely the original name

of Pine Bluff or Dixie (or was very close), both of those were early towns

between Cumberland and Sparta that no longer exist.

EC’s brother-in-law James E. Coats was living in West Point, Lowndes

County, Mississippi in 1860 (assume West Point from 1860 census

description). He was a 27 year old clerk

who lived with a physician – Dr. E. L. Hibler from South Carolina – and also a

single druggist named A. Ball. Another

young 16 year old clerk lived there as well – Joseph Haworth from

Mississippi. James E. Coats was

accurately listed as having been born in Virginia. Interestingly, James E. Coats had no real

estate or personal estate value. EC and

his neighbors were often at West Point.

The town’s humble roots were completely changed when the Mobile-Ohio

Railroad opened for business on 25 December 1857. By 1860, West Point had experienced major

growth since businesses built up around these new railroad stations – and West

Point was a large depot.

During the years leading to 1860,

Mississippi slave owners had been carefully following political

activities. If they were not gossiping

in local taverns, they heard information at courthouses, and also at

church. Note: During the pre-Civil War period only about one-third of the

population was active with the church and religion. They read of political activity in Houston,

Mississippi newspapers “The

Southern Argus" and "The Houston Petrel," which were both strong

Democrat party supporters and supported the slave owning culture. They had a US president who was partial to

slavery but continuing harassment from the north left slave owners feeling

extremely threatened. Their entire world

– lifestyle and livelihood - was dependent on the use of slaves. Nearly all southerners viewed northerners as

abolitionists and therefore were convinced that a northern (or pro-north)

president would eventually end slavery in the United States. Hence many southern state politicians

threatened cessation if the new Republican presidential candidate – Abraham

Lincoln – won the 1860 election. This turmoil made it extremely difficult for

the Democratic political party to choose a candidate and so the party split.

In November 1860, Mississippi

white men (for sure all slave owners) journeyed to court houses to vote for the

16th US president. The ballot, as with

all southern states, did not include the Republican nominee Abraham

Lincoln. Mississippi cast nearly 60% of

its ballots for Southern Democratic Party nominee John C. Breckinridge. Each state followed suit and hence, every

state in the Deep South cast their electoral votes for Breckinridge. But, Lincoln won all the northern states,

giving him enough electoral votes for the presidency despite receiving less

than 40% of the popular vote (still the second worst popular vote total to ever

win the presidency).

Though Lincoln and the Republican

Party had promised not to address the issue of slavery beyond that of newly

added states to the union, the south believed otherwise. The media and southern politicians

embellished the Republican President’s intent and created a mass hysteria among

southerners. In December 1860, South

Carolina voted 169-0 in their legislative session to secede from the United

States of America. The state of

Mississippi soon decided (on January 9, 1861, the 2nd state) that they would

secede as well and become a part of the new nation dividing from the United

States in February 1861 – the “Confederacy” or the “Confederate States of

America.”

A song popularly heard in

Mississippi, starting in December 1860, was called Don the Blue Badge in tribute to the Bonnie Blue Flag, the

unofficial flag of the new Confederacy.

A stanza of the song read:

Tis time to secede – our cause it

is right,

In urging us on to keep foes from

our shore,

We’ll stop not to think, now

danger’s in sight,

But fight as our forefathers have

fought before.

And God in his greatness, in whom

we trust,

With terror will strike our foes

to the dust,

Then don the blue badge, our foes

we’ll defy,

We’ll fight for our rights or for

them we will die.

The following statement sums up

the common sentiment toward the new United States president (in actuality this

was not true) – “The first act of the black republican party will be to exclude

slavery from all the territories, from the DC, the arsenals and the forts, by

the action of the general government.

That would be a recognition that slavery is a sin, and confine the institution

to its present limits. The moment that

slavery is pronounced a moral evil, a sin, by the general government, that

moment the safety of the rights of the south will be entirely gone” (Judge

Alexander Handy, February 1861). There

was also a concern that the constitution was not supportive of slavery since

Southern whites fully believed that all men were NOT equal.

Secession and an ensuing fight

were a part of every conversation in early 1861. Preparations were made to raise an army – the

Confederacy would prepare for a war.

Mississippi men and boys flocked to join the Confederate Army and defend

their newly formed nation. Most were

young but older men did join, especially those who wanted to protect their way

of life – a life dependent on slavery.

On 23 March 1861, EC (at about age 38) was enrolled into the Confederate

Army by Captain W. H. Moore (of the Van Dorn Reserves, Monroe County) at

Sparta, Chickasaw County, Mississippi.

EC appeared on a list of men in a company of soldiers called the Spartan

Band. These were all men recruited from

Chickasaw County, Mississippi. The

Spartan Band initially was a part of the Uniformed Regiment of the Mississippi

Volunteers and would be led by Captain Wesley Mellard. This company was stationed at Marion Station,

Lauderdale County, Mississippi on 30 March 1861.

Note: EC’s young half brothers-in-law – Kellis Richard Hooker (born 28

October 1842) and Lewis Willian Hooker (17 July 1844) – and several neighbors

(among others) – John Richard Cousins (born 1841), James Lafayette Clark (born

circa 1837), Thomas Benton Clark (born circa 1839), Silas W. Clark (born circa

1841), and William L. Cockrell (born circa 1842) – enlisted at Sparta,

Chickasaw County, Mississippi as well.

They were all placed, like EC, in Company K (Spartan Band) of the 13th

Mississippi Regiment. James Clark was a

physician and therefore received a commission as 1st Lieutenant, Richard Hooker

became 1st sergeant within a year, Thomas Clark received a commission as 2nd

sergeant, John Cousins was commissioned a 5th sergeant, and neighbor Silas

Clark was promoted to 4th corporal within a few months.

Note: EC and those men previously mentioned are noted in Confederate

records to have been from an area that was served by the Sparta Post Office. Montpelier was also mentioned several times

in the Confederate Civil War records – Silas and Thomas Clark noted that they

were from an area served by the Montpelier Post Office. Therefore, these records clearly indicate

that EC was not living at Montpelier but in an area between the two small

towns, likely closer to Sparta.

EC became a soldier before any

actual hostilities had begun. His

demeanor and those of the men around him was that of protector, not

fighter. However, that mood was not to

last. War began in Charleston, South

Carolina at Fort Sumter in April 1861.

EC and the Spartan Band would now be aggressors, if the war continued as

it seemed it would, they began to entertain the probability that they would

participate in one or more battles. As

the Army leaders refocused their energies based on an actual war, the

organizational structures of the Mississippi Army changed. On 1 May 1861, the Spartan Band was a company

in the newly organized 13th Regiment.

All companies in this regiment would be led by Colonel William

Barksdale.

Colonel William Barksdale

On 2 May 1861 EC officially

enlisted as a private for a duration of 12 months duty by Captain W. S.

Walker. The Spartan Band was still under

the leadership of Captain Mellard but on 22 May 1861 he retired his

commission. On the same day, Captain

William H. Worthington of Lowndes County was assigned to the Spartan Band. Later in the month, the Spartan Band was

reassigned as Company H (formerly Company K) and would remain under the leadership

of Captain Worthington.

A local Mississippi newspaper

published a notation, on 9 May 1861, of a contribution to Confederate soldiers

who had just volunteered – the local townspeople presented “each member

[soldier] with a beautiful blue badge [Bonnie Blue Flag], bearing the code

[coat] of arms of the State of Mississippi, and the mottoes, ‘Southern Rights’

and ‘For this we Fight.’” This sentiment

honored their men who would fight to uphold their way of life and surely guide

them home safely after defending the new Confederacy. Did they realize the casualty magnitude that

would soon begin? Surely they could not

fathom the death that would occur.

In the first half of May 1861, EC

bid his family and his friends in Chickasaw County farewell. Final arrangements were made for the care of

his plantation. He journeyed north to

Corinth, Alcorn County, Mississippi with his family and arrived on or before 14

May 1861 (records show that the men arrived in Corinth between 13 May and 15

May, only a guess regarding his family).

Volunteers usually arrived as family groups. “Going off to war” was an excellent time to

make a big scene – a public demonstration of strength and courage. EC quite likely received a uniform, a tent,

other odd supplies, and possibly a rifle.

He kissed his wife and children goodbye before they left to journey

home. Note: EC and his neighbor volunteers listed the distance they traveled

from the Montpelier area to Corinth as 130 miles. However, EC’s military record only notes that

he traveled 12 miles to Corinth. EC had

no known connection to any person or location near Corinth, Mississippi. Maybe a third number was inadvertently left

off – like a 0 making it 120 miles.

Since 1846, EC had been involved

with the Chickasaw County militia – the Forty Fifth Mississippi Militia

Regiment – where county men met periodically and trained for service (these

militia units began during the Mexican War and this militia unit was specific

to the Chickasaw County area). Militias

kept US men semi-prepared for soldier duty if a need arose. Mostly, these militia units drank alcohol and

caroused. EC may have thought this “war”

would be very similar. He probably

assumed his 12 month enlistment would never be completed. An aggressive showing by the Confederate Army

should scare the north, end any potential hostilities, and send EC home to

resume his life in the new slave-supportive Confederacy of States.

EC would have traveled from his

home in Chickasaw County to the train station at West Point. From there he advanced by train to Corinth in

northeast Mississippi. His train journey

with his Regiment started at the Corinth train station and followed a first leg

to Jackson, Tennessee. Union City was

another short train ride north from Jackson.

While at Corinth, the 13th

Mississippi Regiment received orders on 22 May 1861 to advance to Union City,

Obion County, Tennessee for training. On

25 May 1861 at 3PM, EC and his company boarded a train at the Mobile & Ohio

Railroad and arrived at Jackson, Madison County, Tennessee later in the day at

8PM. The next day, 26 May 1861, they

boarded another train at 10AM and arrived at Camp Barksdale near Union City at

noon. At Camp Barksdale, the Mississippi

men joined other Regiments and were attached to General Leonidas Polk’s

Army. For nearly two months, EC was

trained to fight as a part of a larger group (EC was present in June 1861 on

the muster as a private under Captain Worthington in the Spartan Band Company

H, paid for service 30 June 1861).

He learned that strength was in

numbers and that he must “hold the line” at all cost. Since formation was so important for rapid

movement and orderly action, soldiers trained by marching. There was very little technology to use – the

idea was for the men to move quickly. So

they marched constantly. EC did practice

firing a rifle. Shooting at targets

imagining “Damn Yankees” across a field was not difficult. And, he practiced using a bayonet when

charging the enemy. Mostly though, EC

and his company marched. Training gave

EC the disturbing feeling that his life may soon be at stake. EC was not fond of being yelled at and

constantly told what to do. Army

leaders, some quite young, demanded the men follow orders. EC had very seldom been barked at during his

life and must have suffered through the harassment by his officers. He was nearly 40 and the only orders he had

ever taken had been from his father and older brothers. EC’s life, in actuality, largely involved

giving orders, not receiving them.

On 9 July 1861, the 13th

Mississippi was ordered to Lynchburg, Virginia.

EC was going back to his birth state.

Two days later, the 13th Mississippi again boarded a train on the Mobile

& Ohio Railroad. They traveled

south, back to Jackson, Tennessee and then on to Corinth, Mississippi where

they arrived on 12 July 1861. The next

day at 9PM, they were on a Memphis & Charleston Railroad train to Iuka,

Tishomingo County, Mississippi. They

arrived there at 3PM on 14 July 1861 and later boarded a train to Chattanooga,

Hamilton County, Tennessee, arriving at 9PM on 15 July 1861. From Chattanooga, they boarded an East

Tennessee & Georgia Railroad train at 7AM on 16 July 1861 and were in

Knoxville, Knox County, Tennessee a short time after noon that same day. From Knoxville, EC and his Regiment were on a

Virginia & Tennessee Railroad train the next morning, 17 July 1861, to

Lynchburg, Virginia where they arrived at 5PM on 19 July 1861.

As soon as they arrived at

Lynchburg, EC’s Regiment was ordered to Manassas, Virginia. They hopped on an Orange & Alexandria

Railroad train at 9PM, passed through Charlottesville, Albemarle County,

Virginia, and arrived at Gordonsville, Orange County, Virginia in the afternoon

of 20 July 1861. The entire Regiment

started their march to Manassas Junction, Prince William County, Virginia at

about 4PM on 20 July 1861 and arrived at Camp Pickens, Manassas Junction about

10PM later the same day. EC and his

Chickasaw County peers were feeling patriotic and ready to fight for their

beliefs, yet apprehensive and likely a bit nervous.

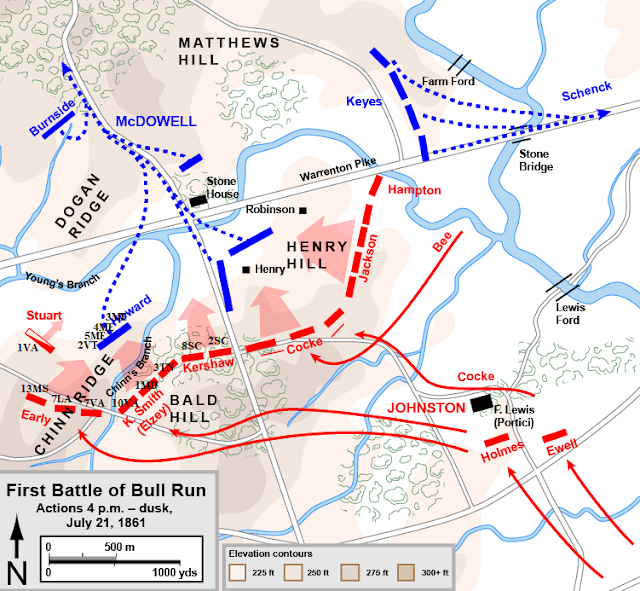

After a short night at Manassas